Benefits for Mondelez International to Expand to Myanmar

1.0 INTRODUCTION This is a report that studies the potential reasons and benefits for Mondelez International to expand to Myanmar. Mondelez International Inc. is a multinational company that revolves around selling well-known snack food brands around the world. Some of these food brands include Oreos, Tiger, Cadburry, Milka, Toberone, Jacobs as well as Halls which are commonly available even within Malaysia.

The company has a market presence in every region of the world although it still has markets not yet expanded to. Take for example, in Southeast Asia the company has yet to have a direct presence in Brunei, Laos, Cambodia and including Myanmar either for reasons of lack of foreseeable profits or discouraging political risks. Myanmar, at one point in time, was a reclusive country with nearly 50 years of political and economic isolation. Today, it is a developing country that is currently undergoing reforms aimed at encouraging foreign direct investment (FDI) (Wong, 2014)[1]. The international community has recognised the reform efforts taken by the Myanmar government and has resulted in the ease of decades-old sanctions towards it particularly by the US (United States) government, European Union (EU), and the Canada (Burke, 2012)[2]. The ease of business entry into the country due to the reforms and removal of sanctions has meant that now is a good time to enter the market and tap into opportunities once untouchable in the country. In fact, many multinational companies have not wasted any time in entering what they see as a gold mine for FDI. Microsoft, Coca-cola, Nissan, and Baker & Mckenzie along with Mondelez’s direct competitors Unilever and Nestle are but some of these MNCs to participate in the gold rush for opportunities. Although still behind countries like Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia, its growth economically has been staggering in the past few years due to the massive amounts of FDI. The growth in FDI brings in an increase in the purchasing power of the average Myanmar citizen which means that there is still a growing market base that is fresh for brand establishment and plenty of undeveloped land for low-cost production facilities. Company Background Mondelez International’s headquarters are in Illinois, United States and its current CEO is Irene Rosenfeld who was also the CEO for Kraft Foods Inc. A very intriguing aspect of this company is the fact that despite being in an age where mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures are common, this company was the result of a demerger that took place in 2011. Based on the Forbes (2013)[3] rankings, the demerger seemed to have paid off since the company in 2013 had a market capitalisation of US$50.1 billion along with being 182nd in the Forbes Global 2000 but most of all the company moved up to 52nd from 63rd last year in the Forbes Innovative Companies. Mondelez International was originally part of Kraft Foods Inc. which had a wider focus that also sold grocery products (Schaefer, 2011)[4]. The demerger split Kraft Foods into two companies, one (Kraft Foods Group that handles grocery manufacturing and processing in North America while the other, renamed Mondelez International, revolved around selling every snack food brand the original held prior to the demerger.

This allowed Mondelez International to adopt a more central focus to its strategy that revolved around a more narrow line of products. Employees prior to the demerger settled on the word Mondelez for the snack food company which combines the words monde (world in Latin) and delez (delicious in short form) as mentioned by Toole (2012)[5]. Toole’s article further goes on to mention that the name will not be used in making new products but will instead act as an idea that the company’s own snack product brands can be associated with.

Since it officially is a part of the original company that existed since 1923, Mondelez International thus inherits all resources and rights to assets and snack food brands that Kraft Foods possessed worldwide even though it has officially only existed since 2012. Objectives The objectives of this report are to:

- Assess Mondelez International’s capabilities in expanding to developing countries

- Evaluate Myanmar’s environment to determine feasibility of expansion

- Determine a feasible method to enter the market

- Identify methods to handle risk effectively

Scope of Report To achieve the stated objectives, the report will cover an environmental analysis of Myanmar through the use of external analysis frameworks such as PESTEL and Porter’s Five Forces. An internal analysis of Mondelez International strengths and weaknesses is the second half of the circle that will be compared with the environment analysis. This will determine the feasibility of market expansion and filter out the most suitable mode of entry for the company. Last, but not least, risk management practices will also be recommended within the report as a means of reducing Mondelez’s exposure to risk in the country. 2.0Literature Review Transition Economy Factors affecting the overall performance of a multinational company (MNCs) are vastly different when comparing transition economies to developed and developing economies.

For one, a transition economy is a market that entirely relies on the recent opening its economy to generate growth through foreign direct investment (FDI). Transition economy will eventually grow into a developing economy but until then it is a market characterised by prevailing levels of hostility, dynamism and complexity that surpass developing ones. Luo and Peng (1999)[6] indicates that transition economies often still have weak regulatory systems, underdeveloped factor markets as well as poor property rights protection by current standards and this contributes to the market characteristics mentioned earlier. Therefore, environmental factors of a transition economy can greatly affect the MNC’s performance in that economy. Take for example, back in 1989 China experienced the Tiananmen Square incident that triggered the mass evacuation of expatriate personnel for many MNCs. This incident shows how transition economies such as China back then are filled with uncertainties that MNCs have to deal with. Bribery Due to that uncertainty and weak regulations as well, bribery is also commonplace within the transition economy and that MNCs must be willing to engage in these activities in order to gain traction in performance. Zhou and Peng (2011)[7] affirmed that the downfalls of bribery will not affect large firms such as MNCs. This seems to attribute to the findings that large MNCs are less likely to get caught conducting bribery compared to small firms.

Thus, large MNCs, who have little risk in the practice, will have the incentive to engage in bribery in order to improve its performance in the transition economy. Furthermore, in doing business in transition economies, MNCs (agents) must also deal with its government (principal) in a principle-agent kind of relationship.

Peng (2000)[8] mentions in comparison to domestic firms, MNCs have greater bargaining power in setting the control levels of the government. The study refers to the time China turned into a transitional economy from the 1970s and had to manage the flow of FDI by MNCs typically by joint ventures. Its government encouraged FDI to gain MNC resources while the MNCs conducted FDI to tap into the market potential of China resulting in conflicts of interest. Therefore, the level of control transition economies attempt to impose will affect MNC’s performance significantly. Organisational Learning From the past few paragraphs, we have concluded that in transition economies, multinational companies face greater levels of environmental turbulence stemming from organisational structures, regulations and markets that are unfamiliar, inconsistent and fragmented respectively. In this case, a multinational company’s ability to learn and adapt to the ever-changing market will also contribute to boosting that MNC’s market performance.

This concept is known as organisational learning and research over the years recognises it as a critical component that influences the performance of international expansions. Luo and Peng’s (1999)[9] research state that experience is the primary contributor to organisational learning. Experience in this case is referred to as the intensity and diversity of exposure to particular market environment. Their research further goes on to mention that MNC’s engaging in a diverse range of activities and for lengthy periods of time gain greater experience effects and that such experience are more significant when operating in transition economies. Overall, greater levels of organisational learning gained from the experience of operating in a transition economy will inevitably facilitate the rise of the MNC’s performance in that economy.

Speaking of which, experience from a particular economy is typically gained from being in that economy for a long period of time. The period of exposure gained by being in a marketplace the earliest can be considered as an intangible competitive advantage that cannot be imitated by rival firms. The longer the experience effect is in the market, the better the MNC can evaluate its risk and reduce its uncertainties as well as develop valuable ties with local partners in that economy while effectively establishing the rules of competition. In order to be the longest player in the game, you have to be the first to enter it, and that brings us to “First Mover Advantages. Advantages MNC’s gain for being pre-emptive to enter the market, Luo and Peng (1998) the benefits to the MNC as being able to dictate the entry barriers for following firms, obtain scarce assets within the economy and effectively gain technological leadership.

They further elaborate those MNCs that pursue first mover advantages are not in the market for short-term profits, but instead seek to establish long-term gains through secured and large market-share dominance of the economy. Whether the first-mover succeeds or fails is another story, but in the case of transition economies, the opportunity to securely establish brand recognition in a brand-fresh market is one that is hard to pass up. Conclusively, these studies show the key importance the environment of a transition economy plays in addition to the usual capabilities the multinational company has in the prospect of performance within that economy. Both the environment of the country and the state of the industry are to be included within the transition economy’s environment. These factors all eventually beg the question of How can a firm take in all of these variables in order to arrive at a suitable strategy that can directly translate into greater performance in transition economies? Perspectives of the Strategy Tripod Due to the depth of research covered in industry-based views and resource-based views, it is most definite that MNCs expanding to foreign markets will have to consider the effects of competition and the firm’s own capabilities in formulating feasible strategies. To elaborate, the industry-based view is a perspective that considers the effects of industry conditions on a firm’s strategic performance. This of course refers to competition levels within the particular industry of a country the MNC is intent on participating in. The effects are noticeable when market entry barriers set by the first-movers of an industry can force a change in market entry strategy.

Looking from a resource-based perspective, this view justifies that the internal conditions of a firm will affect its strategy and performance. No one firm is similar to another and hence why strategies employed by one firm will not necessarily work out the same way for another. Overall, strategic management dictates that a firm’s strengths and weaknesses in relation to market circumstances will eventually decide the final strategy to be executed.

Kogut (2003)[10] criticized both perspectives for leaving institutional factors of a market, both formal and informal, in the background when it is these factors that set the context of competition and the nature of the firms that operate in an industry. Peng and Jiang (2008)[11] state that the institution-based view of strategy formulation is crucial when it comes to operating within emerging economies as the nature of institutions both formal and informal affect the context of competition as well as the nature of firms operating within a market. This perspective views the environmental conditions of a market that affects the strategy chosen by MNCs such as political risks, nature of policies set by nation states as well as the changing cultural values of the local population. Understanding of these factors can lead to proper understanding of the marketplace and thus proper strategy evaluation as well as selection. Strategy Tripod Framework  Figure 2.1 The Strategy Tripod Concept by Mike Peng Combining the three perspectives together brings forth the “Strategy Tripod concept as shown in Figure 2.1. This is a concept helps to address how firms behave in foreign markets. By assessing these perspectives of a market, MNCs can precisely determine the success factors that influence the final strategy as well as the nature of those factors in order to achieve competitive advantage.

Figure 2.1 The Strategy Tripod Concept by Mike Peng Combining the three perspectives together brings forth the “Strategy Tripod concept as shown in Figure 2.1. This is a concept helps to address how firms behave in foreign markets. By assessing these perspectives of a market, MNCs can precisely determine the success factors that influence the final strategy as well as the nature of those factors in order to achieve competitive advantage.

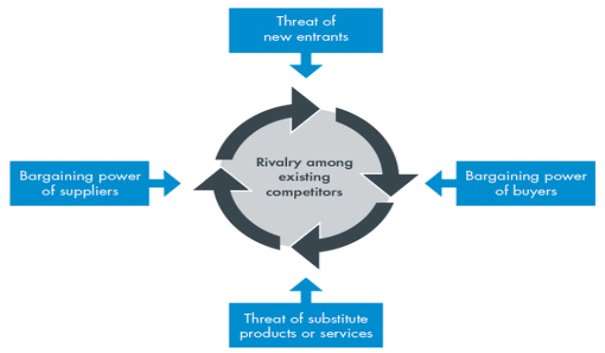

Indeed, the institution-based perspective is the third leg that helps sustains the strategy tripod together with the industry-based perspective and resource-based perspective. This framework is vital for penetrating transition economies since its uncertain conditions can alter the industry playing field and affect how well MNCs can use its resources at hand. Frameworks Applicable to Strategy Tripod In order to sufficiently evaluate the various factors from the three different perspectives, frameworks that are tailored to evaluate each different perspective of the Strategy Tripod will be utilised. This therefore causes the necessity to explain the frameworks to be utilised for this report. Industry-Based Competition To properly assess the industry of an economy, the frameworks of Porter’s Five Forces and the Generic Strategies will be used here. These frameworks help determine the Porter’s Five Forces This framework was created by Michael E. Porter in 1979 with the purpose of determining factors that affect the profitability of a particular industry. The framework revolves around five forces as shown in Figure 2.2 (hence, the name of the theory) that assess a market in terms of both competitive intensity and its attractiveness (CGMA, 2014)[12] . When combined with the internal analysis of an organisation, the Five Forces can be used to understand where is the MNC’s strengths in an industry lie currently as well as where it can go to develop new strengths or enhance current positions.  Figure 2.2Porter’s Five Forces Starting with the threat of new entrants, this force refers to the likelihood of new firms entering an industry.

Figure 2.2Porter’s Five Forces Starting with the threat of new entrants, this force refers to the likelihood of new firms entering an industry.

Markets that are profitable with inevitable attract newcomers who will attempt to steal market share and thus reduce the profitability of the various existing firms in an industry. Unless there are significant entry barriers arising from either policies, economies of scale, or capital requirements to protect incumbents, there is very little to impede the entrance of these newcomers and thus cause high levels of threat which reduces market attractiveness. Besides that, threat of substitute products or services also affects how the industry functions. This force refers to the magnitude of alternatives to a product or service that affect how likely customers will switch between substitutes when factors such as price change.

For example, customers can easily switch between different brands when alternatives are nearly or equally similar to one another which represent a high level of substitute product threat. In this instance, firms cannot easily charge higher prices for a product customers know to have cheaper and equivalent alternatives. Bargaining power of buyers in an industry also plays a key role in assessing the circumstances of an industry. This refers to how influencing buyers can be in pushing down prices. Usually determinant of several factors such as the number of buyers in the industry, value of each buyer to a firm as well as switching costs buyers face when deciding to switch. When buyers are few and concentrated while switching costs for them are low, the buyer’s bargaining power is considerably high and selling prices will fall.

Furthermore, similar to the buyer’s bargaining power, the supplier’s bargaining power plays are key role in the overall competitiveness of the industry. When suppliers to an industry can drive up prices, costs of goods sold will increase which reduces the overall competitiveness of firms within that industry.

The power of suppliers to do this is reliant on whether the suppliers are in concentrated numbers, of large size and strength with high switching costs. The opposite of these three variables signal low bargaining power of suppliers. The final force of this model looks into the rivalry among existing competitors. As the intensity between existing rivals in an industry heightens, returns become lower due to increased costs in competing with one another and thus leading to lower profitability for each firm. Intensity is usually determined from size and number of existing competitors, life cycle stage of the industry and also the level of differentiation between products of different firms.

Higher intensity occurs when there is no leading firm in an industry, products do not outstand from one another or the industry reaches its peak leading to a lack of growth in the customer base. Porter’s Generic Strategy Another framework developed by Porter that describes how firms within an industry can position itself in order to achieve competitive advantage by using 3 types of generic strategies based around the dimensions of market scope and competitive advantage. These three strategies are referred to as cost leadership, differentiation and focus and will strengthen the position of the firm in regards to the Five Forces.  Figure 2.3Porter’s Generic Strategy Starting with cost leadership as shown in Figure 2.3, this focus of strategy is attributed to broad scope and cost-based competitive advantage. It suggests that a firm should focus on low costs and prices in order to successfully compete within its industry. With little differentiation but a wide target market, a firm would attract a massive number of customers by offering greater value for price compared to its rivals in the industry. The firm would generate profits mainly through savings gains from productions and logistics efficiency. Wal-Mart is a prominent practitioner of the cost-leadership strategy which is basically sell cheap to nearly everyone.

Figure 2.3Porter’s Generic Strategy Starting with cost leadership as shown in Figure 2.3, this focus of strategy is attributed to broad scope and cost-based competitive advantage. It suggests that a firm should focus on low costs and prices in order to successfully compete within its industry. With little differentiation but a wide target market, a firm would attract a massive number of customers by offering greater value for price compared to its rivals in the industry. The firm would generate profits mainly through savings gains from productions and logistics efficiency. Wal-Mart is a prominent practitioner of the cost-leadership strategy which is basically sell cheap to nearly everyone.

Moving on to differentiation, this aspect of generic strategy suggests that a firm should focus on distinguishing itself effectively from its competitors in order to compete successfully.

[1] Wong, M 2014, Myanmar aims to increase foreign direct investment by 10% to US$3b, media release, 22 January, Channel News Asia, viewed 14 February 2014, <https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/business/myanmar-aims-to-increase/963526.html>.

[2] Burke, J 2012, MNCs enter Myanmar’s door, media release, 5 February, Hindustantimes, viewed 14 February, <https://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/mncs-enter-myanmar-s-door/article1-806920.aspx>.

[3] Forbes 2013, MondelA„“z International, viewed 14 February 2014, <https://www.forbes.com/companies/mondelez-international/>.

[4] Schaefer 2011, Kraft Foods Latest To Split In Year Of Breakups, media release, 4 August, Forbes, viewed 14 February 2014, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/steveschaefer/2011/08/04/kraft-foods-latest-to-split-in-year-of-breakups/>.

[5] Toole, JO 2012, Kraft to rename snack unit ‘Mondelez’, media release, 21 March, CNNMoney, viewed 19 February 2014, < https://money.cnn.com/2012/03/21/news/companies/kraft-name-change/>.

[6] Luo, JQ and Peng, MW 1999, Learning to compete in a transition economy: Experience, environment, and performance, Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 30, no. 2, viewed 22 February 2014.

[7] Zhou, JQ and Peng, MW 2011, Does bribery help or hurt firm growth around the world?, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, vol. 29, viewed 22 February 2014, <https://www.utdallas.edu/~mxp059000/documents/Peng12APJM_Zhou_29_4_Dec__907_921.pdf>.

[8] Peng, MW 2000, Controlling the Foreign Agent: How Governments Deal with Multinationals in a Transition Economy, Management International Review, vol. 40, no. 2, viewed 22 February 2014, <https://www.utdallas.edu/~mxp059000/pdf/Peng00MIRauto.pdf>.

[9] Luo, JQ and Peng, MW 1999, Learning to compete in a transition economy: Experience, environment, and performance, Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 30, no. 2, viewed 22 February 2014 <https://www.utdallas.edu/~mxp059000/pdf/Peng99JIBS.pdf>. [10] Kogut, B. 2003. Globalization and context. Keynote Address at the First Annual Conference on Emerging Research Frontiers in International Business, Duke University. [11] Peng, MW, Wang, DYL, & Jiang, Y 2008, An institution-based view of international business strategy: a focus on emerging economies, Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 39, no. 5, viewed 23 February 2014, <https://www.utdallas.edu/~mxp059000/pdf/Peng08JIBSWangJiang39(5)pp920-936.pdf>. [12] CGMA 2014, Porter’s Five Forces of Competitive Position Analysis, viewed 23 February 2014, <https://www.cgma.org/Resources/Tools/essential-tools/Pages/porters-five-forces.aspx>.

Cite this page

Benefits for Mondelez International to Expand to Myanmar. (2017, Jun 26).

Retrieved March 3, 2026 , from

https://studydriver.com/benefits-for-mondelez-international-to-expand-to-myanmar/

Stuck on ideas? Struggling with a concept?

A professional writer will make a clear, mistake-free paper for you!

Get help with your assignmentLeave your email and we will send a sample to you.

Perfect!

Please check your inbox